Growing fast and profitably without hitting the ceiling

How omni-channel strategy can grow your DTC startup: a simulation case study

Many DTC (direct-to-consumer) startups end up selling their products through retail in an effort to go omni-channel and reach more customers. Recently, Daily Harvest announced their expansion to grocery stores in partnership with Kroger, and even back in 2018, Plated rolled out their meal kits nationwide in Albertsons shortly after the acquisition. This is not uncommon.

In this post, I explain using simulations why they are doing this in relation to growth hacking and how going omni-channel can help them grow fast and profitably in the long run. I also describe the formal growth hacking framework from a statistical perspective.

💡 For context, I highly recommend you read my previous post:

Early adopters of a DTC product can generate a significant word-of-mouth without any investment in marketing, resulting in an influx of new customers and investment. This initial growth often leads to pressure from investors to expand aggressively to justify their investment.

However, after saturating the original target market, a DTC startup may struggle to maintain its growth trajectory without broadening its customer base. Unfortunately, the new wave of customers may not be as engaged with the product as the early adopters, leading to lower revenue and reduced customer retention. To continue growing, the startup may need to increase its marketing spend, which in turn increases the cost of acquiring new customers.

In the meantime, the startup's rapid early growth attracts competitors, prompting them to adopt aggressive tactics. These rivals decrease prices and invest heavily in promotions. Consequently, the cost of acquiring new customers eventually exceeds their actual worth to the startup. As a result, the company faces a depletion of funds, causing investors to become hesitant in providing further capital. In response, the startup may opt to take drastic measures, slowing down growth and reducing the workforce to control cash outflows. While the startup may manage to survive, its value will plummet, leading investors to incur significant losses.

So how can DTC startups manage the ever increasing cost of acquisition and turn their growth into sustainable profit over time? Grow slow and your competitors will catch up; grow fast and you’ll quickly hit the ceiling. I built a toy financial model1 to illustrate these two growth scenarios and explain how omni-channel strategy, expanding product offerings to retail and other customer channels, if done well, can help DTC startups grow fast and profitably over time.

Modeling the business

Take an example of a simplified DTC startup that sells eco-friendly bamboo toothbrushes online on a subscription basis.

Assume the following metrics:

Average CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost) of $9. We also give $1 discount to first time customers on their first order (this is usually the case for subscription businesses). Our fully loaded CAC is therefore $10 total.

Average LTV (Lifetime Value) of $100 over 2 years with our business.

After 1 year, 25% of customers are still buying from us. These remaining customers will still quit at a rate of 0.25% per month over time after their first year.

40% gross margin. We make $40 per $100 of revenue.

Monthly churn rate of 5%. This means 5% of our customers quits the subscription in the first month.

Monthly reactivation rate of 0.75%. Most customers won’t take us up again after they quit their subscription. Reactivation stays constant devoid of seasonality.

Since we make $40 in profit for every $10 we spend to acquire a customer, we have 4:1 LTV:CAC ratio once a cohort of customers has been with us for 2 years which is considered healthy. $30 net profit2 per customer helps pay for rent and salaries of our employees and hopefully make a windfall for our investors later down the road.

Two additional assumptions—

Traffic curve

We almost always see a diminishing return on customer acquisition (e.g. traffic, clicks, conversions) as we increase marketing spend (e.g. CAC, CPC, CPA, CPM) in auction-based channels. The rate of increase in the number of customers per month decreases over time as we increase the marketing spend.

For non-auction channels, we pay for them at a fixed price for a placement in magazine or a specific time length at a given region and time in TV. A physical storefront pays a flat rent no matter how many customers they attract.

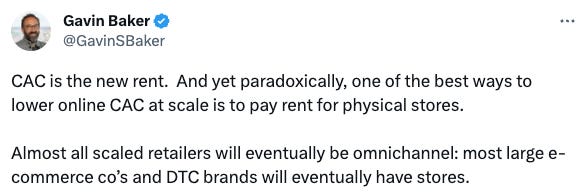

In a way CAC is the new rent. Online businesses need to constantly remind customers of their business and get them to make repeat purchases of their products by spending large amounts on advertising (on Google, Facebook, and other channels) because people forget your brand. This ongoing expenditure is similar to paying rent for a digital storefront. On the other hand, retail and brick-and-mortar stores, especially in a high-traffic location, benefit from constant visibility as people walk by and see their store and products all the time.

In fact, CAC is worse than rent because it gets less efficient the more you spend. If we were to sell entirely through retail stores and increased our spend 3x, we can roughly expect to acquire 3x the number of customers, not less.

Early stage startups can leverage low level of CACs (shaded area in gray) so it might be sensible to be online only since they only have to acquire small numbers of customers to grow quickly3, but eventually after a certain point, they’ll saturate the target market, and acquiring new customers and retaining them will become much more costly and inefficient.

Cohort model

I generated a reasonable monthly cohort model over the next 9 years. A cohort in our case is a group of customers who first subscribe in a given month. We track the percentage of remaining subscribers from the cohort over time. For simplicity, I only show the curve for the first cohort, i.e. those who first subscribed in month 1, year 1.

Growing slow 🐢

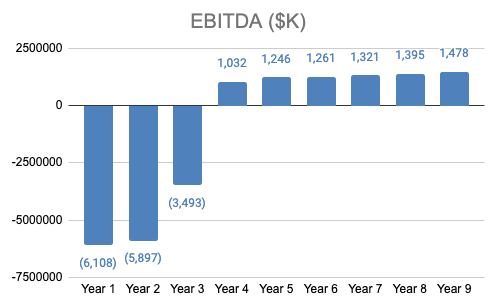

Based on the above assumptions, I ran a simulation of revenue and EBITDA4 over the next 9 years. Let’s assume we acquire 3K new subscribers each month.

This looks okay, but we can do better. Your investors will pressure you to grow faster in order to deter your competitors and quickly make a huge return on investment.

Growing fast 🚀 and hitting the ceiling

Now let’s assume we are acquiring 30K new subscribers each month, 10x more than before. As a hyper-growth startup, we’re tempted to show investors the potential of our business by riding the J-curve and outrun our competitors.

The problem with growing too fast is you end up raking all potential adopters of your product too early that you eventually reach the ceiling. At this point, the cost of acquiring new customers exceeds their actual worth to the startup. It gets worse if we have a transactional business where we need to advertise to convince customers to make repeat purchases5.

So we’re currently a business between 3-4% EBITDA stuck and can’t grow beyond $42MM revenue. What can we do to grow fast and profitably then?

Growing fast and profitably 💰

We saw from the simulations above that if we go too slow we end up being consumed by competitors, and if too fast, we end up in a speed trap. We need to reach more customers in a cost-effective way, and the omni-channel strategy allows your potential customer to buy your product from anywhere in any way they want, not just through subscription.

Many customers want to try a product in a low risk way before subscribing later, i.e. they want to touch and feel your product before buying online, or even buy at the last minute in a store, while others will never subscribe but buy your product more flexibly on-demand either online or offline. In our bamboo toothbrush business, we assumed 25% of subscribers are still buying from us after one year, but for the remaining 75%, a rigid subscription model will not be a good fit.

Having a presence in retail and brick-and-mortar stores helps raise brand awareness6 and lower CACs over time. These stores can serve as a “mini-warehouse” to stock up your product, making delivery to customers faster when they do order online compared to delivery from a distant regional warehouse, as well as pickup locations for the customers. All these cater to diverse customer behaviors and needs across online and offline touch points, improving the overall customer experience.

Some growth hacking basics

The equilibrium number of customers (a.k.a. the carrying capacity CC of the business) equals the number of new customers acquired today divided by the rate of lost customers today. That is, if we acquire A customers per unit time and have P(churn) per customers per unit time, the equilibrium number of customers CC equals:

We can also rewrite the expected (average) LTV as the product of N the number of purchases, orders, or boxes for example in a typical e-commerce subscription business and AOV average order value. If we assume independent trials, then N = 1 / P(churn)7.

In either case, reducing P(churn) is paramount to increasing expected LTV and CC. Retention8 therefore is probably the most important outcome we want to optimize even before optimizing for acquisition. How can we get our customers to continue engaging with our products? Ultimately, we need to improve the core customer experience9.

Omni-channel strategy allows us to achieve steady growth in the online media channel while maintaining a healthy and efficient level of CACs and to attain higher customer retention over time by significantly improving the overall customer experience bridging the gap between online and offline channels.

We don’t necessarily have to bring all offline customers to online and get them to subscribe to our business because their needs are inherently different. What matters is crafting a seamless customer experience that engages your customer from online to offline, and vice versa.

About this newsletter

I’m Seong Hyun, and I’m a data scientist, machine learning engineer, and software engineer. Casual Inference is a newsletter about data science, machine learning, AI, tech startups, management and career, with occasional excursions into other fun topics that come to my mind. All opinions in this newsletter are my own.

Typically, a financial analyst in your FP&A or strategic finance team will do this type of what-if scenario analysis in Excel.

Net profit = LTV - CAC

Compared to traditional retail, DTC model allows you to serve your customers better by natively understanding them using first-party data and continuously improving your products upon that learning. This alone can be a significant advantage to start and sustain a business online for years without needing to go offline in retail.

EBITDA = (Gross Profit - Total SG&A) / Revenue x 100 (%), where Gross Profit = Revenue - COGS (Cost of Goods Sold) and Total SG&A is a catch-all category of expenses that aren’t COGS such as marketing expenses.

Even with subscription, most customers will stop buying because DTC products have a lot more friction than say OTT and music streaming (media subscriptions) because you’re receiving a physical product every week, month or quarter, which causes fatigue. DTC startups try to reduce this fatigue from receiving the same product by diversifying the existing portfolio such as introducing new product collections.

Early stage DTC consumer brands benefit from the positive impact of paid acquisition on customer traction, but the successful ones later diversify and invest in branding, organic search, public relations and word-of-mouth. Selling through retail stores is one way of raising brand awareness.

Assume an independent Bernoulli (i.e. there can be only two outcomes each trial—purchase or no purchase) trial (e.g. purchase, order, box) with the probability of churn p = P(churn) (hence, the probability of a purchase is q = 1 - p). Then the number of purchases before the first churn X follows a geometric distribution. The expected value (i.e. average) of the number of purchases before the first churn is 1 / p.

Here’s the story proof:

Let m be the expected value of the random variable X. There can be two cases. Either the customer churns the first time, in which case X = 0 (no purchase) happening with probability p, or the customer makes a purchase the first time happening with probability q. In the latter, the customer already made one purchase, and everything restarts the next time (i.e. in the subsequent trial we are back with the same problem of whether the customer makes a purchase or churns), so X = 1 (purchase the first time) + m (problem repeats). Solving for m, we have that m = (1 - p) / p. However, what we actually want is N = E(Y) = E(X + 1) that includes the first churn, so N = 1 / p.

Retention is different from reactivation. In retention, a company targets customers who are at risk of churn, changing their decision using retention offers or service improvements; on the other hand, in reactivation, the company targets customers who have already churned, re-engaging with them.

I say this all the time. For example, if you’re a restaurant owner, before you direct your attention to anything else (e.g. interior design, customer service, promotions), your foremost priority should be crafting exceptional food. Without great food, you won’t be able to retain your customers in the long run. Focus on the core thing that matters to your business and then expand to “last mile” experience.